Guðmundur Thoroddsen: Tittlingaskítur - Hverfisgallerí

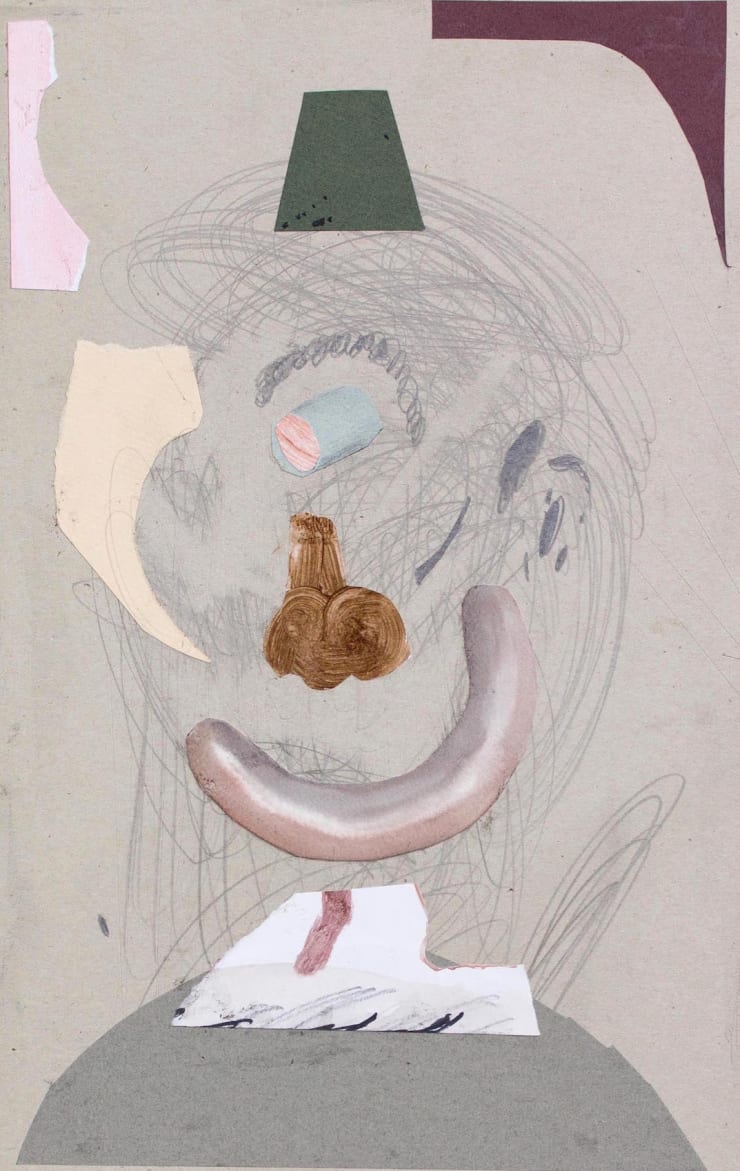

The world we encounter in Thoroddsen’s cut out pictures is strange but striking. We see odd men wandering about in a directionless space, some wearing suits and others in their underwear, but all of them very preoccupied; they are focused and busy doing something though it is hard to see exactly what. Thoroddsen himself doesn’t mince words, saying that they are just “stupid males doing something that they think is very important but is really just onanistic nonsense.

Though these pictures are definitely humorous it is hard not to see in them a social critique targeting the patriarchal traditions that value men’s work and interests above all, even though many of them have proven time and again that they have no idea what they are doing and often fail spectacularly, harming both themselves and others. Cut outs and collages are an excellent medium for delivering such messages and that was how they were frequently used when artists first started to employ the method a century ago. In the hands of Dadaists such as Hanna Höch the collage became a powerful political weapon where advertisements and magazine photographs were reused to target authorities and the ruling classes. After World War II collages became popular again, proving useful in criticising and ridiculing Western consumerism and society, e.g. in the works of Richard Hamilton and Erró. Thoroddsen’s pictures differ from theirs in that he doesn’t reuse printed material directly but paints or draws his figures before cutting them out. The effect, however, is similar and the humour just as sharp.

Cut outs and collages are not, of course, just about the content. This is a visual medium that demands every bit as much discipline as painting or photography and Guðmundur is acutely aware of this, having himself worked in many media, including painting and sculpture. His pictures are far from being just a jumble of images. They have well-defined depth and dimension though Guðmundur plays around with proportions and the size of his figures. The construction can seem a little loose at first glance but is in fact perfectly calculated to underline the pompous futility of his male characters.

Though there is a great deal of humour in all this, there is also a bitterly ironic, even angry, edge to Guðmundur’s work. There is something infantile about these funny little men. They strut around as though the fate of the world depended on them, they bully and push and feel that everything they do is supremely important, if not heroic. The earthenware sculptures in the exhibition underline this delusion of the patriarchal mentality. They are urns, resembling sporting trophies, decorated with what looks to be penis symbols. In this way – Guðmundur seems to be telling us – men reward themselves and each other, thus maintaining the myth of their superiority and importance.

Jón Proppé